Meet Gique Zach Lanoue

Freelance Cameraman, Multi-Media Artist, Creator of Landscan

Tell us about your experience at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston.

From the beginning, my goal as an artist was to show the world in a way that it had not been seen before, which is still what I strive for in my work today. I was lucky to have access to fine art classes through the colleges my mother worked at. Just like all kids, I drew and painted for fun. I just didn’t stop when I got older.

The School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston was an appealing place for me because it doesn’t pigeon-hole you into choosing just one medium. Mixing them together was encouraged. My course load was all over the place: Sometimes I’d have print making and drawing in the morning and then performance and photo in the evening.

To make my homework easier I figured out that I could combine all my assignments into one project. For example: I would photograph a performance then make a drawing from the photo and take elements of both to make a screen print. This is called cross-mediation, which means translating a piece of art into different media, like making a drawing from photograph, and it’s how I got through art school.

That was a major breakthrough. It was like learning to bake a cake—the chemistry between the ingredients can create something greater than the sum of its parts. Now my process for making art is like a recipe that is always evolving.

What inspired you to create the Landscan Project?

I think my passion for photography stems from curiosity. The camera is the best tool for exploring the world and sharing what you find. I always want to see things from a different perspective and with a camera I can extend what is possible for me to perceive. I got the idea for the Landscan process while watching a TV show where oceanographers were making a photographic map of a sunken shipwreck using cameras on a submarine. The set up was simple: the camera was over the ground pointing straight down and took photos while the submarine moved over the ocean floor. Kind of like mowing the lawn. The photos then were laid out and lined up in Photoshop.

I thought while I was watching this, “Hey I could do that!” So I put together a rig to hold my camera 15 feet over the ground looking straight down, used a remote to click the shutter, and went out into the backyard to try it out. After I figured out how to align the camera without looking through the lens, the resulting images became much more clear and defined. The final images are composed of between 80 and 300 hundred photographs that I layer together in Photoshop.

I learned later that this approach is almost identical to a scientific process called photogrammetry, which involves taking many images from an airplane, drone, or satellite and arranging them into a photo map. This is how Google Earth makes their interactive maps of the planet.

Not having access to an airplane, I scaled down the process to make it work for me and now have the ability to make what look like aerial photos. I also take advantage of the fact that the image isn’t taken all at once, which allows me to move objects and people around the space while I am shooting. I choose subject matter that is appealing in aesthetic and social perspectives. In other words, I am very selective about what I shoot and make sure that the location can hold up to the close inspection and scrutiny that an enlarged print will demand. Photogrammetry, on the other hand, is mathematically precise imagery that does not select subject matter based on aesthetic reasons.

At the moment, Landscan is my fun personal project that I do when I am not working for someone else. Exploring strange places and making images that fascinate people with the world that is around them is enriching in a spiritual sense. But it is not without its difficulties. While making a Landscan image near Death Valley this winter I fell and my camera landed in a field of boulders, smashed and totally gone. This happened just after I took sun-bleached bones from a rotting cow corpse and got sucked into quicksand up to my thighs while taking photos. This series of events seem to have some greater mystical significance that I have yet to understand. So much so that I returned the bones to the cow’s corpse just in case I had upset any forces or spirits. This loss came at the height of a creative spree and was difficult to deal with. To be without a camera made me realize how deeply embedded it was in my life. It’s true what they say: “You don’t know what you’ve got ’till it’s gone.” Now I have a deeper reverence for my camera and how it allows me to perceive the world around me.

What does being a gique mean to you?

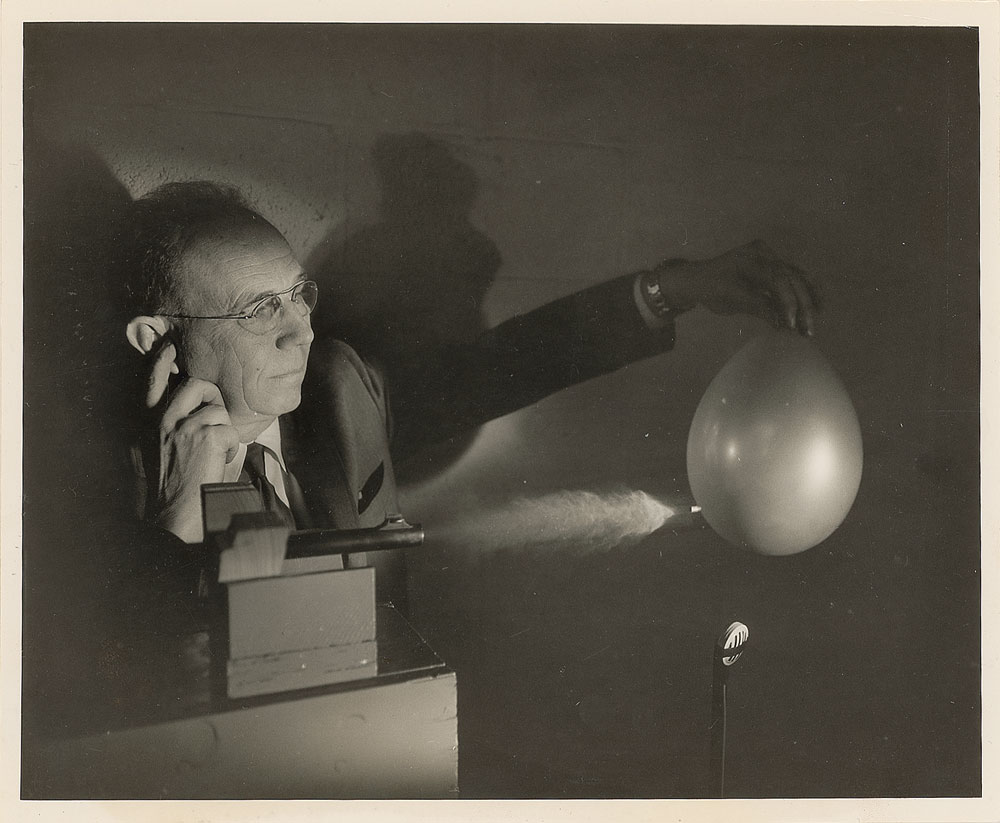

Science and cosmology fascinate me, but I lack the mathematical skills to get very deep into it. What I lack in math I make up for in visual/spatial reasoning that I can use to understand many of the concepts being researched today. I think it’s the artist’s job to absorb his or her surroundings and interoperate them using visual language and free expression. In many ways, artists and scientists are not all that different. They look to push the limits of what can be known and experienced. They think outside the box and experiment with unknown variables. They bring their findings to a community that benefits from that participation. Photography is in the grey zone between art and science. Most of the technological advancements in photography were for conducting scientific experiments (check out Harold Egerton and Eadweard Muybridge).

Once artists get their hands on new technology, it extends those artists’ palates. Photography is the most basic form of remote-sensing equipment, which is essentially a way of collecting data from an object or phenomenon without physically touching it. A camera is really a powerful piece of scientific equipment that you can make art with.

In terms of the different mediums and elements that I use, I like to think of them as tools or means to an end. Like using the right tool for the job, I use the medium that best suits the idea I want to express. In the end, it all comes down to what you see in front of you not the process you use to get there.

Being a gique means being able to find unseen connections between seemingly separate ideas or things. It could refer to someone who looks at what we know and can see what isn’t there. Someone who is doing things that have never been done. Art and science are so similar that, taken out of context, documentation of experiments and their results look very similar to contemporary art. Which makes sense considering both artists and scientists are interested in pushing the envelope of experience.

What words of wisdom would you like to share with other artists?

If you are like me and have many different passions, my advice is to combine them together into something new. For example, I love looking at satellite imagery. I also love making photo-collages so I’ve combined the two and made something different. You can think of yourself as a DJ, cutting and warping different ideas to form a new one. Or like a geneticist, selectively breeding compatible ideas together to bring out desired traits.

Making it as an artist is not an easy task. You’ve got to be resourceful, dedicated, and on your game. Becoming a famous artist is harder than getting into major league baseball and most famous artists only “Make It” years after they’re dead. If you are pursuing art you should be doing it for your own enjoyment because the likelihood of becoming a famous artist is slim. Besides, most of the truly great art out there comes from people who make it simply because they want or need to. Simply for the act of it. Having friends that I can construct a visual dialogue with keeps me resilient. We take inspiration from each other but also learn from each other’s mistakes. Being an active member in a community of artists and onlookers gives your work meaning in the real world. The Internet is a great medium for sharing and has many art communities within it so there is no excuse for making art in a void when we are more connected than ever before. Once you see people resonating with your creations it reaffirms your whole life. To me, that’s when you’ve “Made It”.